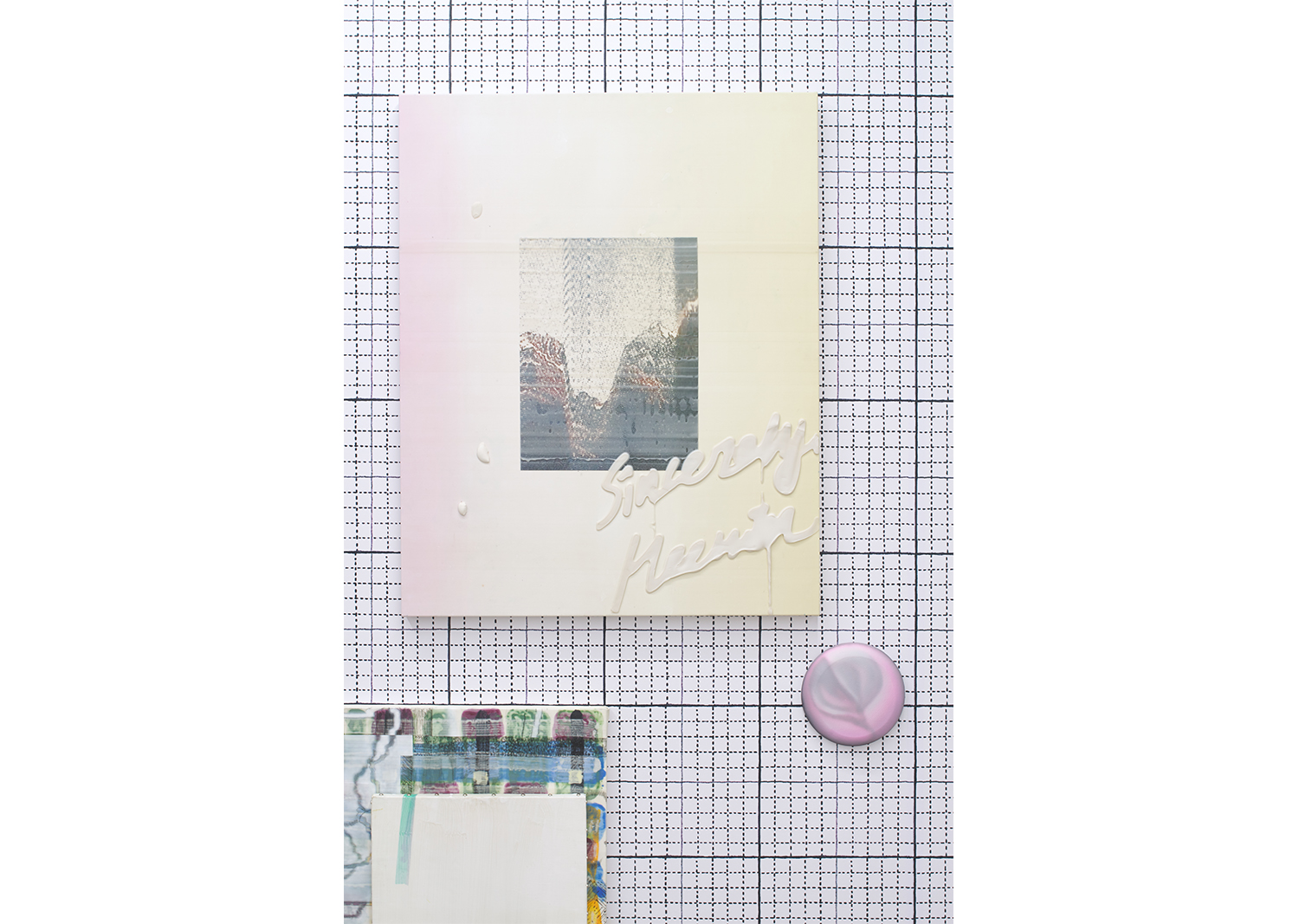

Heemin Chung Solo Exhibition : If We Ever Meet Again

페이지 정보

Date. 2020.06.25 - 2020.08.14페이지 정보

Place. 021galleryContents

Heemin Chung Solo Exhibition : If We Ever Meet Again

Today’s ‘encounters' take on various forms. It may be in the form of physical contact, it may exist as a single idea, it may be a plan, or it may be a coincidence. Encounters could be repeated or a one-time event. Does the word 'encounter' still have the same emotional value in a world where the conditions that mediate everyday do not presuppose objects that exist as physical entities, and increasingly become data for analysis and prediction?Perhaps its plurality (a form of language that represents the behavior or state of two or more people or things) is no longer a necessary condition. “If We Ever Meet Again” began from questions about various new conditions of encounter, and is an attempt to compare the poetic and deceptive sensations created by accumulating the experiences of encounters without objects.

If

We Ever Meet Again:

A Chung Heemin Solo Exhibition

| Understanding Unseen Time

| Hong Leeji, exhibition planner

If

We Ever Meet Again explores

how emotional senses can be conveyed under conditions where an artist’s

presence is unrevealed, using a series of experiences in which the everyday

event or act of “meeting” comes to possess new emotional values and

implications. With this exhibition, Chung Heemin considers the forms in which

an artist’s body and presence – previously absent from the exhibition medium,

where the conditions for a “meeting” may no longer apply – are left behind

together with moments from the past, employing substance as an analogy for the

new sensory states stimulated within unfamiliar meetings and experiences.

To live as an artist is to

require time. David Lynch has said that to produce an excellent painting in one

hour, a person needs at least four hours of undisturbed time – and in this

sense, the “past” associated with a painting does not only refer to the time

that the artist spent painting it. The painting that we encounter in a gallery

exists in a finished state, and so our imagination of the time leading up to

its completion could be seen as an appreciation process in which we seek to

understand the image in a unified sense. The form and tempo of brushstrokes and

layering of images in a painting are expressions of the artist’s movements as

he or she approached it. A painting includes layers of time limned by the

artist’s body as he or she took big or small steps back or hunched his or her

body; it is inscribed with the presence of an artist applying strokes with

quick, dancer-like movements or repeating the same gestures over and over like a

form of ascetic practice. This accumulation of time and movements only achieves

completion as a painting once an overall narrative has been introduced.

Chung Heemin’s paintings are the

result of a process that takes digital representation as its starting point.

Her process of creating images on a screen with a program and then removing

them from the screen and transplanting them to the canvas could be described as

one of representing the synesthetic state of images existing in digital form,

while images that have lost their sense of time and narrative through digital

manipulation are rendered physically through the borrowing of the artist’s

body. During this process, Chung diversifies the “artist’s body” as something

involved in painting, with each aspect playing a different role. Just as Andy

Warhol attempted a transformation of strategy and means to transcend the limits

of contemporary production methods by applying the industrial printing approach

of silkscreen – satisfying the artistic

drive by synchronizing his own body with the machine – Chung Heemin achieves a

more expansive, borderless infinitude of the canvas through the introduction

and synchronization of her own body within the screen. The “question” concerns

what happens when the image is taken back out of the screen after its

synchronization and rendering. In this respect, Chung makes active use of her

own body.

With her first solo exhibition Yesterday’s Blues (2016) and her Kumho

Museum of Art exhibition UTC-7:00 JUN 3PM

On the Table (2018), Chung sought to give expression to the issues she

faced with pictorial representation, as well as the conflicted circumstances of

the contemporary creative environment and her own wrestling with it. She generated

collisions as she represented her own notes about painting on the canvas, or

summoned virtual reality situations into reality to deploy unrealistic events

in physical space – and in the process, the gallery would be transposed into a

setting for temporary representation, existing in a state of “mixed realities.”

From there, she went on to actively display her post-processing efforts as she

added thickness and roughness to the image and applied coating or additional

layers. This may have been a gesture, as the artist herself has described, of

attempting to use active physical intervention on the part of the artist as a

way of adding a sense of real-time unfamiliarity and reality to a surface

representing a digital image as reality’s disproof of the virtual – an approach

based on her interest in states that lack a tactile element.

In Eve (Samyuk Building, 2018) and

Young Korean Artists 2019: Glass Liquid Sea (National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Korea, 2019), the artist filled the gallery walls completely,

while erasing the presence behind the canvas.

Faced with an image that lacks walls and supports, we experience a sense

less of viewing a painting than of being drawn into the scene. In this respect,

Chung’s paintings achieve their completion on the ground. To determine where to

stop and how much to include the canvas, the artist selects the canvas size and

the dimensions and form of the image, after which she zooms in or out on the

virtual world within the previously established screen. Her artistic process,

with its sequence of erasing, editing, and obscuring within what is both a

collection of data and a virtual environment, thus achieves more of a narrative

of completion once the artist’s decisions and choices have been taken into

account, along with the gallery environment where the finally completed state

is placed. For that reason, her work is not completed in the studio. For the

most part, we encounter pictures through printed images or data files on our

mobile phones. As a result, we often overlook the sides of the artwork, or the

gap between the wall and canvas. As we have grown accustomed to the repeated

experience of encountering images on Instagram or in publications, the gap

between “artwork as cropped image” and “canvas as physical presence” has only

increased. A painting in a gallery may be conveyed with a different meaning or

image depending on whether the lighting used is daylight color, warm white, or

natural white, while differences in the viewing conditions based on whether the

work is placed on a white wall, or what scenes the viewers encounter walking

through the gallery, result in each of those viewers having a different viewing

outcome.

Chung

Heemin’s paintings have weight to them. Indeed, anyone who has seen one of her

works in the gallery may have noticed the bulk of the canvas and frame. That

sense of weight and presence may appear all the more accentuated when we are

made aware of the process of the artist gathering and choosing among digital

images before transplanting them into reality. The flat, depleted images

undergo a process of being removed from a screen and being represented on a

canvas, with the artist adding texture to show the weight and presence of

reality. At times, her images arrive in the forms of acrylic sculpture,

canvases, screens, and books; the depth and weight of her world of manipulation

vary according to the medium that they drift into. In the end, we take the time

to meditate as we seek to understand and surmise the unseen. Imagining and

understanding what cannot be seen is thus a difficult endeavor, but an absolutely

worthy one.

instagram

instagram artsy

artsy